Warring Parties: Voices of Patients in Pain Vs. “Opioid Crisis”

So many of us have pain management issues. We are fighting the doctors and the state laws and the insurance companies. The “opiod [sic] crisis” is an illegal drug problem; it is not a prescription problem for chronic pain patients. However, we are the ones who suffer. An increasing majority of doctors are scared to prescribe. I am scared every time I go for an appointment because I am afraid they will cut back my medication. ~Inspire member

In July 2018, Kathleen Hoffman, Senior Health Researcher and Writer at Inspire and I wrote an article for ‘STAT’ based on socio-linguistic content analysis of 140 de-identified, aggregated comments about pain management from several cancer communities on Inspire.1 Summarized in a short article, “Opioid stigma is keeping many cancer patients from getting the pain control they need,” it received over 100 comments from patient, caregiver and medical professional readers.

Here I’ll provide more detail about the study and address some of the comments of our readers.

Cancer pain

A 2017 review of pain management in cancer patients with bone metastases states, “Cancer-related pain is notoriously under-reported and under-treated, despite the availability of many therapeutic options.”2

Cancer can cause intense pain in fact, moderate to severe pain is common for patients with metastatic bone disease. Cancer pain is one of the worse feared aspects of the disease and unfortunately its prevalence remains high.3 A meta-analysis of research conducted between 2005 and 2014 found that 66% of patients with metastatic disease reported pain. In addition over 55% experienced pain during cancer treatment and almost 40% of all cancer patients reported moderate to severe pain on a pain rating scale. 4 Another study found that even though the quality of pharmacologic pain management has slightly improved in the last decade, one in three patients on average do not receive pain medication considered appropriate for the intensity of pain experienced.5

What is the experience of people with legitimate needs for pain medication?

The voice of cancer patients

A qualitative, sociolinguistic review of 140 posts on Inspire by 100 patients and caregivers dealing with lung, bladder and advanced breast cancer found that these patients are experiencing stigma from both healthcare providers and society in general.

Access to pain medication: Healthcare providers

Stigma impacts access to prescriptions for pain medications. Patients with cancer report that their doctors hesitate to prescribe opioids, due to concerns over addiction. In addition, restrictions on refills and the timing of refills impacts the consistent use of medications to treat pain, clearly contradicting even the advice provided by the National Cancer Institutes’ own materials:

“Take your pain medicine dose on schedule to keep the pain from starting or getting worse. This is one of the best ways to stay on top of your pain. Don’t skip doses. Once you feel pain, it’s harder to control and may take longer to get better.”6

Members of Inspire’s cancer communities are having trouble maintaining consistent use of pain medication. Overall, this makes patients feel frustrated; as if they are being treated like drug seekers when their pain needs are real and management necessary. The language patients used to describe their experience accessing medications and the the stigma that accompanies it included: “make me feel like a druggie,” “I use a very low dose,” “treated like a pill seeker” and “I am not part of the oxycodone EPIDEMIC.”

Use of pain medications: Societal stigmas

While stigma from healthcare providers can impact access, it is stigma from society that impacts use. Many Inspire members with cancer fear becoming addicts and worry about withdrawal symptoms. They are also concerned about what their use of high doses or multiple pills says about them. This results in their choosing to live with pain rather than using opioids. They also worry about using opioids for a “long period of time”, even though “long” is not defined by the patients.

The number of prescribed opioids has also been discussed. In our analysis, patients felt that one opioid, taken when necessary, was acceptable. Taking two opioids–using them consistently rather than for breakthrough pain– is stigmatized. To minimize the experience of stigma, patients would qualify their posts, describing their opioids as “very low dose.”

Unfortunately, even when a member is still in pain, the community treats their reducing or “coming off” opioids as a success and a reason for pride.

Messaging about addiction and dependence from industry seems to be leading to confusion and misunderstanding. Some patients report that their healthcare providers have told them that cancer patients cannot become addicted because they “don’t get high.” Others are saying that if one needs increasing doses of opioids, they are addicted; still others say that it means that they are becoming tolerant or dependent on drugs.

Patients often suggest cannabinoids as an alternative to opioids. They are positioned as being safer (better side effects) and are viewed with fewer stigmas than opioids.

Finally, some caregivers may be withholding pain medications from patients because they are worried about addiction. When they raised this concern on Inspire, other members advised against withholding pain medication saying managing pain is more important than addiction. However, it is unknown if the caregivers follow this advice or allow their family member to remain in pain.

Patient advocacy

There are cancer patients who fight the stigma by advocating for proper, controlled pain management; reinforcing that the stigma against using opioids should not interfere with care decisions. Their message to other members is not to feel guilt for taking pain medication. Moreover, they recommend pain management clinics and pain management teams who are experts in pain control so that access to treatment is not negatively impacted. These recommendations stipulate that oncologists, although excellent in their treatment of cancer, are not necessarily knowledgeable in using narcotics for cancer care.

Patients who are not feeling stigmatized express confidence in their opioid use. They base their conviction and the legitimacy of their pain management choices on their knowledgeable pain management physicians. These patients feel part of a team that is both instructive and supportive. Instructive aspects of these team interactions included explanations of how opioids work, what addiction and dependence means and what patients should expect from their opioid treatment. Descriptions of the supportive facets of the team’s interactions included help with side effects, discussions of patient’s pain, offering multiple options for dealing with the pain and periodic dosing reassessments.

Comments from STAT readers

The comments to the STAT article overwhelmingly supported the experiences revealed by Inspire members. For example an RN commented,

“I was recently near tears over one of my terminally ill patients who needed ever-increasing doses of fentanyl and morphine. His physician told him he would not increase his dosages again unless he agreed to accept hospice services. The physician said his reasoning was that he was afraid for his license and investigation for prescribing high doses. Unfortunately, the patient was coerced into agreeing to hospice, before he was psychologically ready for that decision.”1

Another patient wrote in the comments:

“I myself are going thru this. I have stage III metastatic malignant cancer. Im in almost constant pain. My pain meds work for about 1 hr after they get into my bloodstream. After that i have 4 more hours before i can take any more (1 tab every 6hrs).”1

Pitting patient against patient

Many commenters pointed out,

“Cancer patients are not the only ones feeling stigmatized because if needing pain control. Patients with neuropathy, degenerative spine issues, and many others feel this too….especially when required to be urine tested month after month. We have many senior citizens requiring around the clock pain control who have to see their doctor every 28-30 days to be urine tested and get a new prescription. No refills allowed, and some of these people have to travel long distances in all sorts of weather. This is not acceptable.”1

Some commenters expressed anger that the article didn’t address all chronic pain sufferers.

“YOU’RE SPEAKING ONLY OF CANCER PATIENTS ! Why? Do you know that nearly 5 times more peaple with CRONIC DIBILITATING [sic] PAIN. GET NO PAIN MEDS AT ALL. DO YOU EVEN COMPREHEND WHAT IT’S LIKE TO BE IN CONSTANT PAIN AT THAT LEVEL???? THIS IS PURE TORTURE FOR US..JUST AN INSANELY BLIND MEDICAL SYSTEM”1

The frustration that chronic pain and people experiencing cancer pain feel is vented on other patients with mental health and addiction problems as seen in this comment on the STAT article

“It’s such b.s that we as patient’s got to pay for druggie loseres [sic] that will still get their drugs on the street. If they want to kill themselfs [sic] let them .they do nothing positive for society anyway let them od an do us a favor.”1

The “opioid crisis”

There has been extensive media coverage of the opioid crisis; a Google search for the phrase “opioid crisis in the news” yields over 27 million results in .40 seconds. Yet the media coverage continues to emphasize prescription opioids, when in fact, there has been a decline in opioid prescribing: from 2006 to 2016 the rate of prescribing of opioid pain relievers has fallen by 46.8% and physicians are becoming more cautious with prescribing.7

Indeed, the CDC describes the overdose epidemic as coming in waves over the past 19 years:

“The first wave began in 1999 and includes deaths involving prescription opioids. The second wave began in 2010, with rapid increases in heroin-involved deaths. Finally, the third wave began in 2013, with significant increases in synthetic opioid-involved deaths – particularly those involving illicitly-manufactured fentanyl (IMF) and fentanyl analogues.” 8

Today, at least half of the drugs that are causing deaths are heroin, illicit fentanyl, cocaine and methamphetamines, the CDC states.2

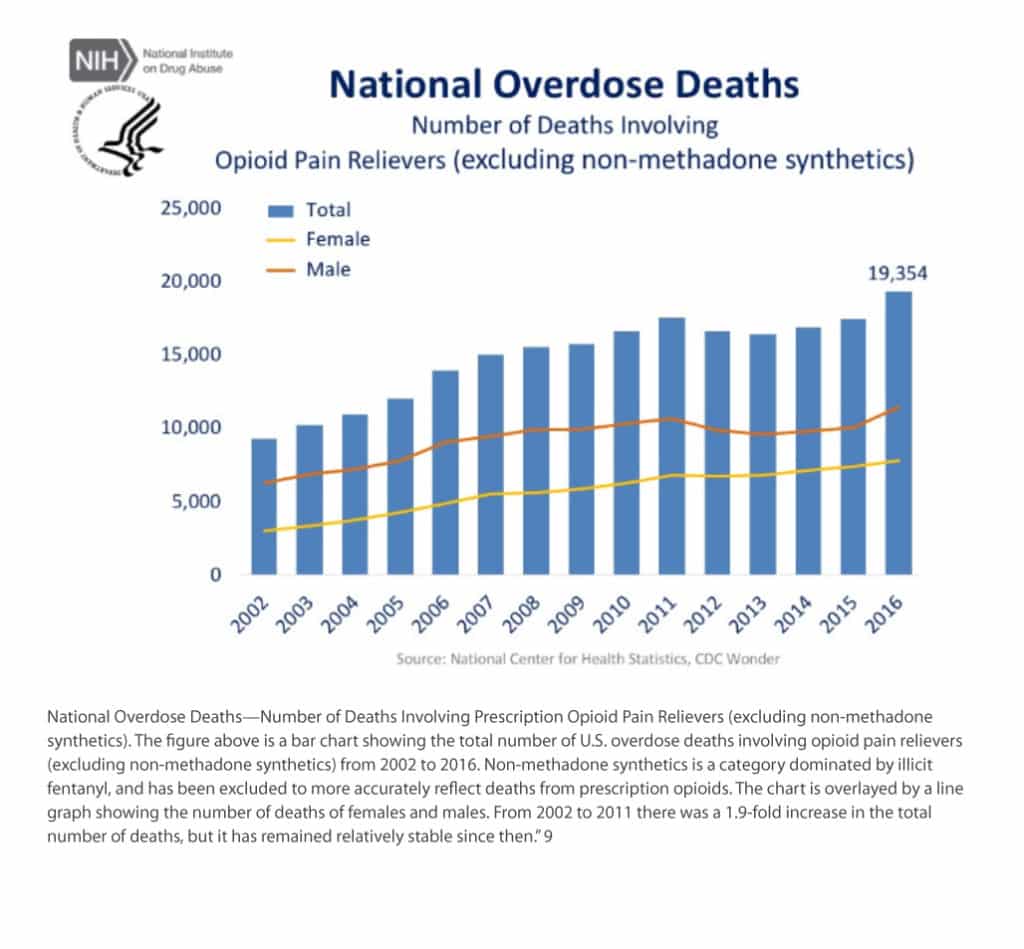

As the chart above shows, since 2011 the number of deaths from prescription opioids has remained stable. Deaths have increased in non-prescription opioid use, primarily due to mixing medications and non-prescription tainted fentanyl.

As the chart above shows, since 2011 the number of deaths from prescription opioids has remained stable. Deaths have increased in non-prescription opioid use, primarily due to mixing medications and non-prescription tainted fentanyl.

Prior to 2000, a pain management crisis existed. Scientists who studied pain management found that as many as 70% of cancer patients in treatment or in end-of-life care experienced unalleviated pain. Similarly, they found issues with pain management after in-patient surgery and among the aged in nursing homes.10

Named a major medical problem, poor pain management became synonymous with poor medical care. In 1999, The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (a non profit that certifies hospitals and health care programs in the US) launched new standards for pain management. Prescribing pain medication became mandatory for hospital accreditation.10 This is also when pain assessment tools began to be used in earnest.

Today, due to the stigma created by the opioid epidemic or opioid crisis, we may be seeing history repeating itself. In our study, cancer patients experience stigma from both healthcare providers and society. As evidenced by the comments to our STAT article, patients with chronic pain are also experiencing this stigma.

Unfortunately the Joint Commission for Accreditation has backed away from its 2001 accreditation standards on pain assessment, with statements like,

“The Joint Commission does not endorse pain as a vital sign, nor has the concept ever been part of accreditation standards….The Joint Commission has never endorsed use of pain “satisfaction scores” for national, public or any other purpose other than an organization’s internal quality improvement….Joint Commission standards have never required the use of drugs to manage a patient’s pain, nor have they ever encouraged clinicians to prescribe opioids….Joint Commission accreditation standards have never required organizations to mandate that clinicians measure pain on a numerical scale or treat patients to “zero pain.”11

Conclusions

Pain management is not being addressed adequately for cancer patients and as STAT readers stated, for patients living with chronic pain.

Patients in our study seemed to experience inoculation or protection from the opioid stigma when treated at pain management clinics or by physicians specializing in pain management. Unfortunately, not every patient has access to these professionals. Education of pharmacists, oncologists, internists, family practitioners, surgeons and other physicians and healthcare providers on pain management for people dealing with cancer and chronic pain is needed. Furthermore, in our study, patients with cancer and their caregivers need support and education about pain and pain management. Awareness campaigns supporting pain management in cancer and chronic pain could counteract the stigma of opioid use that patients with legitimate need are experiencing.

Inspire offers a trusted community to patients and caregivers. Our goal with this blog, this website and our content is to provide the life science industry access to the true, authentic patient voice. In so doing, we support faithful operationalization of patient-centricity. Take a look at our case studies, eBooks and news outlet coverage.

Reference:

1 https://www.statnews.com/2018/07/06/cancer-patients-pain-opioid-stigma

2 Cancer ResearchUK (2018). Coping with cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/coping/physically/cancer-and-pain-control/causes-and-types

3 van den Beuken-van Everdingen, M., et.al. (2016). Update on Prevalence of Pain in Patients With Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 51(6), 1070-1090.e9 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.340

4 Pastrana, T. et.al. (2017). Pain Treatment Continues To Be Inaccessible for Many Patients Around the Globe: Second Phase of Opioid Price Watch, a Cross-Sectional Study To Monitor the Prices of Opioids. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 20(4). http://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2016.0414

5 Greco, M. et.al. (2014). Quality of Cancer Pain Management: An Update of a Systematic Review of Undertreatment of Patients With Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. (32)36, 4149-4154. http://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/JCO.2014.56.0383

6 US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institutes. (2014). Support for people with cancer: Pain control. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/publications/patient-education/paincontrol.pdf

7 The Centers For Disease Control and Prevention. (2017) Annual Surveillance Report of Drug Related Risks and Outcomes United States 2017. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2017-cdc-drug-surveillance-report.pdf

8 The Centers For Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Opioid Overuse: Understanding the epidemic. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

9 https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates

10 Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. (2003). Improving the quality of pain management through measurement and action. Retrieved from http://www.npcnow.org/system/files/research/download/Improving-the-Quality-of-Pain-Management-Through-Measurement-and-Action.pdf

11 https://www.jointcommission.org/facts_about_joint_commission_accreditation_standards_for_health_care_organizations_pain_assessment_and_management/